“Schools shall provide continuing education for those students who are determined to need additional time to achieve the outcomes defined in KRS 158.6451, and schools shall not be limited to the minimum school term in providing this education.” (KRS 158.070)

That requirement has been part of Kentucky law (KRS 158.070) since Kentucky Education Reform Act of 1990: if students need more learning time, our schools must add that time. The statutory language calls that time “continuing education,” but state regulation, state budgets, and common practice call it extended school services – or ESS.

ESS makes a classic offer of equity: an offer to get the learners what they need to keep learning, even if they need something different from other learners in their class, grade, or age group.

Alas, it’s an equity proposal that has encountered major difficulties since the beginning.

Transportation was a very early problem. How will learners who need additional learning time get home after buses have departed? There are options, but none of them are easy or low-cost or as flexible as “provide more time” can sound before you notice the logistics.

Money quickly became another difficulty. 1993 funding was scheduled to reach the equivalent to almost $100 million in today’s dollars – until a SEEK shortfall was spotted late in the 1992 legislative session. The program took a big cut right then, and summer school options were dramatically reduced as a result. The program has been further eroded over the years, with the 2022 appropriation of $24 million only a pale shadow of the original concept. +

Outcomes shifted. ESS was created to serve students who needed more time to “achieve the outcomes defined in KRS 158.6451.” The 75 “Valued Outcomes” were one of the first 1990 KERA implementation steps, with entries like “students use research tools to locate sources of information and ideas relevant to a specific need or problem” and “students use appropriate and relevant scientific skills to solve specific problems in real-life situations.” For a brief period long ago, the statewide concept was that educators would all become skilled in understanding where students were in relation to each outcome. That would not be about standardized test scores: it would be about professional judgment based on students’ authentic work on meaningful assignments. And ESS would be a support option applied when educators identified that students who were not yet meeting an important expectation. That “outcomes-based” design plan burned out quickly. Many educators pressed for a more detailed breakdown of their responsibilities at each level, and political opponents argued that the outcomes promoted bad values. The Valued Outcomes were renamed Learner Outcomes, then reorganized as Learner Expectations, and then converted into an introduction to the Core Content for Assessment. Sometime in the last decade, they were deleted from regulation as no longer important or relevant.

So, how does ESS work now? It varies by school and district. I found some good examples on school websites, including these:

- Eastside Elementary in Harrison County offers tutoring for reading and mathematics three days a week.

- Maurice Bowling Middle School in Owen County provides “extra help in various subject areas” on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons and has tentatively scheduled “Saturday Schools” on four Saturdays this year “to help students who are failing the current nine weeks.”

- Adair County High School plans to deliver Extended School Services “Virtually (via Google Classroom and Google Meet) and In Person this year…..to students who are at risk of failing, need instruction on missing assignment content, or need additional instruction to grasp the content needed in the classroom.”

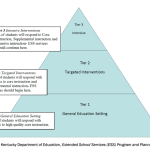

More broadly, the Department of Education’s most recent ESS guide includes a credible proposal to use ESS as a key element in plans for intervention tiers. The “tier” idea calls for instructional approaches in which instruction is designed from the outset with core instruction offered to all and added tiers of support to be deployed based on evidence of which students will benefit. That tiered approach is getting some important traction as a workable systematic approach to planning ahead to support in order to keep all students on track. The graphic below is from that ESS Guide.

These ideas about what ESS provides still leaves the puzzle of how $24 million can serve 640,000 students. It is less than $40 per student. If the design plan follows the triangular graphic and aims at serving about 20%, it’s still under $200 per learner in need of support. It might cover 10 hours of help a year, plus some transportation.

For a student who is persistently struggling with multiplication or geometry or core scientific practices or major elements of civics and geography, is that the right level of support? That seems unlikely.

I think the original ESS sense of scale deserves new life, with the resources to offer multiple weeks of added learning for students who can benefit. We can aim high for all students if we have flexible methods for reaching them and are building equity in the form of making sure all learners have the resources they need to keep learning. ESS is still the right name for the equitable practice of being flexible with the precious resource of time.

An added note: As our schools work on addressing the impact of COVID, they will temporarily have extra federal dollars to address learning effects of the pandemic. That may provide valuable opportunities to think about how deeper ESS investments could work for the long term.

Comments are closed.