Since 2019, for Kentucky’s African American students, Hispanic or Latino students, and students of two or more races, our public schools have:

- Increased gifted and talented identifications

- Increased participation in Advanced Placement and dual credit courses

- Reduced both over- and under-representation problems in identification of students with disabilities

- Reduced disproportionate use of in-school removals and out-of-school suspensions

This is good news. The changes are not huge, but they move in the right direction.

This is also good news that does not fit expectations. From beginning of Kentucky’s battle with COVID-19, many observers expected opportunity losses for all students and worse losses for students in groups that have been historically underserved. On these opportunity measures, Kentucky schools instead delivered gains for these groups of students even as the pandemic raged around them.

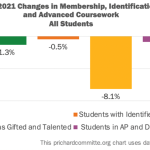

To put the equity improvements in context, there were some declines for all students. Enrollment dropped 1.3%. Given that drop, it’s probably positive that identification of students with disabilities declined by less than that, as did enrollment in Advanced Placement and dual credit courses that let students experience college-level work and gives them a chance at earning some college credits. It’s certainly concerning to see the greater drop in identification of gifted and talented students (using a count that also includes students in the primary talent pool).

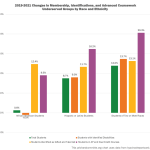

With that context, here’s what happened for our three largest historically underserved race/ethnicity groups.

This, I think, is all good news. All three groups have been underrepresented in gifted programs and advanced courses, and the way to change that is for their participation to increase faster than their enrollment: just what the chart shows.

For identifying disabilities, the situation is a little more complex. African American students have been overidentified while Hispanic or Latino students and students of two or more races have been under-included. That means a small decline in African American Identification, as shown in the charts, looks like a positive step, while growth faster than enrollment is right for the other two groups.

There’s more.

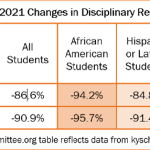

Discipline resolutions that remove students from their classrooms can weaken opportunity for those learners, either through out-of-school suspension or in-school removals. In 2019 and earlier years, those removals happened disproportionately to all three groups and with especially disturbing frequency for African American students.

The pandemic changed that, of course. In virtual learning, in-school removal isn’t really workable. If in-person learning is designed to keep students together with a single set of classmates, the removal remedies also don’t work well. Dramatic drops in school use of those methods should be no surprise, but take a look at how the reductions showed up for different groups.

The greatest reductions happened for African American students, the group most subjected to this kind of consequence. Hispanic and Latino students and students of two or more races also saw reductions greater than for white students. Here again, the changes all bend toward equity.

This news also doesn’t mean that now opportunity is fairly shared. At the end of this post, I’ve shared a table showing disproportions in these metrics and in the more detailed breakouts of types of giftedness, in kinds of disabilities, and in progress from enrolling in advanced courses to qualifying for college credit based on that work. Building full equity will require major work in the coming years

And it certainly doesn’t mean that we’ve achieved full equity. Getting all learners the resources they need to keep learning is a challenge in any setting, and the pandemic has made all the challenges greater. The outcome data released in September confirms that we’ll need added investments (in creativity and commitment as well as funding) to deliver for students after recent major disruptions. That challenge will surely require all hands on deck.

This news does mean, though, that Kentucky schools improved equity of opportunity for historically underserved racial and ethnic groups while COVID-19 was making every improvement harder. That’s impressive, and we should be impressed.

Comments are closed.