JANUARY 2020 \\ ROBERTSON COUNTY

At first, the idea of a four-minute scavenger hunt seeking examples of basic geometry terms seemed like a dud. Students in Deana Rosenthal’s 4th grade classroom in Robertson County first responded by looking at each other as much as surveying the room.

Soon, however, someone noticed perpendicular lines on the door frame. Or the parallel stripes of the classroom flag. Students jumped from their seats to trace the mortar between the blocks in the wall — the right angles of perpendiculars. The flagpole was declared a line segment.

By the time their teacher said that only 15 seconds remained, groups of students buzzed around the bookshelves, pointed down at the intersecting edges of the floor tiles and gazed up at the borders of the ceiling tiles.

Answers popped out everywhere they looked.

Math classes at Robertson County routinely connect abstract lessons with hands-on practice. “There’s always an application problem that goes with the skill,” said first grade teacher Ashlee Shugars. The same morning as the 4th grade scavenger hunt, her students were using large paperclips to measure various items, helping them understand about units of measure.

Making sure students envision math concepts builds a stronger understanding of what they are studying — and why, Shugars said.

“At such a young age, they are very concrete thinkers,” she said. “They require lots of movement and touching objects that help them see how to measure. For example, where you properly align a ruler with an object or how to read how many units. Allowing them to practice with real-life examples enhances and builds that concept.” Engaging practice, along with opportunities to review and refresh recent learning, are priority strategies for increasing proficiency levels across the elementary grades.

In 2013, education results in Robertson County were far different. Financial troubles put the district on the state’s radar. The district had repeated in corrective action status for not meeting the annual yearly progress on the state accountability system. A state management audit found significant weaknesses, from administrative areas to classroom learning. The district was placed on four years of state assistance.

FOURTH-GRADE TEACHER Deana Rosenthal discussed basic geometry terms with her students in Robertson County.

It emerged on a different track. New math and reading curricula were chosen to increase the level of challenge and application. Practices were added for monitoring student performance and providing quick assistance when pupils fell behind. A 2017 comprehensive audit by the state reported “significant improvement” based on state test results. By then, the district’s accountability label was “distinguished/progressing.”

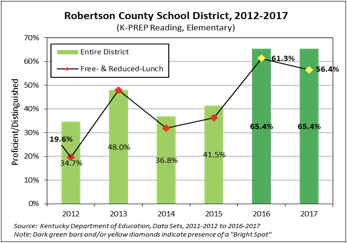

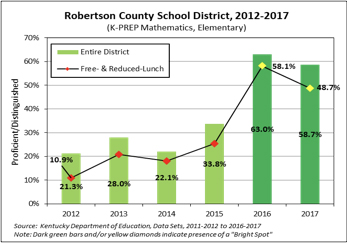

Last year, Robertson County stood out as a “bright spot district” in a statewide analysis of student performance by the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Kentucky in partnership with the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence. The study, examining state test results from 2012-17, used local socioeconomic data to establish a predicted level of performance.

The report identified 12 districts that significantly exceeded those expectations based on overall average test scores in at least one of the years studied. In addition, the study only identified districts where less-advantaged students showed steady progress over the span including a better-than-expected outcome in 2017. Robertson County was the only district that made the list in two categories: elementary math and reading.

Superintendent Sanford Holbrook said that the wake-up call of state assistance provided the 400-student district an opportunity to reinvent itself. Following through on tough challenges wasn’t easy, he said: “When things got tough and people said ‘Let’s go back to the old way,’ we didn’t. We wanted to do what was best for our kids, and we stuck with it.”

Robertson County is now focused on improvement by closely monitoring classroom performance and ensuring more students are mastering learning standards. Building relationships, supporting teachers to deliver a rigorous curriculum, and monitoring results are priorities in the turnaround, he said.

“One big thing that pushes us is our data — what can we do, what’s not working, what can be helped,” Holbrook said. “We’ve got to improve every day. Education is learning, and learning is an everyday process.”

Engaging practice, along with opportunities to review and refresh recent learning, are priority strategies for increasing proficiency levels across the elementary grades.

The superintendent arrived in Robertson County as the state assistance process began. “I wanted them to know I was going to support them and really be active in the education process,” he said. “I told them we can’t change our past — we are where we are — but we can change the future.”

The district started fresh by seeking rigorous reading and math curriculum that would both challenge and engage students.

Treva Woods, a Robertson County native in her 22nd year teaching in the district, said that while the school used the state intervention as a new beginning, it started as a daunting challenge.

“The question was how are we going to reach every kid? It was a very big mountain to climb, and it took the whole staff,” she said. The faculty pulled together and continues to fine-tune practices like how it plans intervention for students when they fall behind or varying teaching approaches to students with different learning styles or interests.

“It used to be you’d teach it, grade it, get it covered,” Woods said. “Now we look at data from assessments, and the students analyze their data as well. That’s been a big change in helping our students succeed.”

Students who have been part of the school during and after state assistance said they have noticed the change in classwork and expectations.

“It’s a lot better for me because it gives more hands-on experience with stuff and helps me learn better,” 8th grader Devin Craig said of the current approach to reading and math. “I’ve been doing a lot better with geometry.” Regular opportunities to learn in small groups or different ways to understand concepts makes concepts stick, he said.

Lilan Chmura, a 7th grader, noted that the school is eager for student input, apt to celebrate achievements, and has added opportunities for students beginning in middle school to be aware of how well they are prepared to meet college- and career-readiness targets. “I think it’s cool that in 7th grade they are already preparing you for huge life experiences,” she said.

Now we look at data from assessments, and the students analyze their data as well. That’s been a big change in helping our students succeed.

— Treva Woods, teacher

Woods, who now teaches science and social studies across elementary grades, said the school has come a long way in improving student learning.

“Success has come from students learning in small groups and breaking things down through differentiation. We look back six or seven years ago at how we thought it was hard,” she said. “Now it’s just how we teach. We do what’s best for our students and identify ways to meet their needs. We try to make it as real world as possible, and we make time to ensure that they understand the content. If they don’t get a specific topic and you just move them on, the students get further behind.”

State officials said Robertson County benefited from being open to advice on how to improve. “They are an example of accepting help and collaborating,” said Dr. Kelly Foster, the state’s associate education commissioner who works with districts under state assistance. “They are a totally different district,” she said. Foster credited the superintendent for emphasizing student achievement gains as well as building support for change in the school and community and making sure the district was intentional about how funds were spent.

Holbrook said that challenges remain. The district’s first steps focused on eliminating novice performance in reading and math and building a solid foundation in elementary grades. As elementary teachers continue to build rigor in classes, the school, which serves students through high school, is working to build more support. It is also emphasizing learning and opportunities beyond high school.

“We want to keep moving our kids in reading and math, but we are also tackling ACT issues,” Holbrook said. (The school also boasts an ambitious agriculture program that creatively covers several career-focused paths.) “We’re starting to see our kids talk about their futures and about getting better ACT scores because that will help them to get money to go to postsecondary,” he added.

Devin, the 8th grader, is interested in a future in construction, which makes his geometry skills seem more important. He said his school is pointed in a good direction. “We are given a lot more opportunities to learn,” he explained. “The school now breaks it down more, it helps students understand more and helps them excel.”

FIRST-GRADE STUDENTS in Robertson County use large paperclips to measure items on a worksheet as a way to understand units of measure.

\\

USING DATA TO FIND BRIGHT SPOTS DISTRICTS

Last August, the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Kentucky examined statewide student test results and local socioeconomic factors to uncover “better than expected” district-level performance. The report was designed to identify school districts worthy of a closer look. The results were designed to highlight proficiency by all students, high achievement by students who qualified for free- or reduced-price meals, and districts demonstrating improved performance a six-year period. The study found 12 “exemplar” districts.

“Since school districts are likely to reflect the underlying economic conditions of their surrounding communities, the socioeconomic characteristics of Kentucky’s school districts are as diverse as the state itself,” the report found. “This is evidenced by the percentages of less‐advantaged students in the Oldham and Owsley County School Districts, which are, respectively, 22 and 89 percent. Likewise, the average per pupil expenditures in the top quartile of districts is one‐third higher than those in the bottom quartile — $13,380 compared to $10,140.”

“Since school districts are likely to reflect the underlying economic conditions of their surrounding communities, the socioeconomic characteristics of Kentucky’s school districts are as diverse as the state itself,” the report found. “This is evidenced by the percentages of less‐advantaged students in the Oldham and Owsley County School Districts, which are, respectively, 22 and 89 percent. Likewise, the average per pupil expenditures in the top quartile of districts is one‐third higher than those in the bottom quartile — $13,380 compared to $10,140.”

The report, produced in partnership with the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, is “best viewed as a statistical sieve designed to narrow the list of candidate districts worthy of closer examination,” it noted.

Several districts highlighted in the report will be profiled in this on-going Bright Spots blog. The blog offers a classroom-level view of promising practices and trends in student learning across Kentucky.

The visit to Robertson County yielded the story of a district that has overhauled its approach to teaching and learning in the wake of state assistance, which ended in 2017 — largely overlapping the period where data was examined for the UK report.

In Robertson County, several priorities emerged:

\\ Student engagement connected to real-world applications;

\\ Closely monitored individual progress where data is used to plan interventions;

\\ Efforts to build relationships and communication to focus everyone involved on increased proficiency; and

\\ Recognition and celebration of individual and group progress.

Each month, the BRIGHT SPOTS blog showcases impressive learning in Kentucky schools.

READ OTHER STORIES IN OUR SERIES ON DISTRICTS IDENTIFIED IN UK’S ‘BRIGHT SPOTS’ REPORT

\\ MAKING PROFICIENCY A CONSTANT at Monroe County

\\ AN ONGOING CHALLENGE at Jenkins Independent

ABOUT ROBERTSON COUNTY SCHOOL \\

ENROLLMENT: 400 in P-12

KEY DEMOGRAPHICS

RACE: 3% minority

INCOME: 68% eligible for free/reduced price meals

DATA NOTES

\\ By population and by area, Robertson County is the smallest county in Kentucky. The district operates a single school for all of its students, with the central office attached.

\\ On 2019 K-PREP reading tests, 62.4 percent of Robertson County elementary students scored proficient or better, about 8 percentage points above the state average. About 54 percent of economically disadvantaged students scored proficient or better on 2019 tests. In 2014, the school’s proficiency rate in elementary reading was 37 percent.

\\ On 2019 state math tests, 57 percent of Robertson County elementary students scored proficient or distinguished, about 8 percentage points above the state average. Among Robertson elementary pupils who qualified for free- or reduced-price meals, 48 percent scored proficient or better on 2019 tests. In 2014, the school’s proficiency rate in elementary math was 22 percent.

\\ In both elementary reading and math in 2019, the school’s proficient-or-better rate for economically disadvantaged students was almost identical to the state’s average proficiency rate for all students.

Comments are closed.